Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease (COVID-19) which resulted in the human COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 can be spread from human-to-human via small droplets that are expelled when an infected individual coughs, sneezes or speaks. People can become infected if they inhale these droplets or transfer them to their face after touching a contaminated surface.

COVID-19 was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019.

Clinical signs

Symptoms typically occur five to six days after infection, but can take up to 14 days. Most people that become infected will develop mild to moderate illness and recover without hospitalisation. The elderly and those with underlying health conditions are at greater risk from developing serious symptoms. WHO defines the symptoms as below.

Most common symptoms:

- Fever

- Cough

- Tiredness

- Loss of taste or smell

Less common symptoms:

- Aches and pains

- Sore throat

- Diarrhoea

- Headache

- a rash on skin, or discolouration of fingers or toes

Serious symptoms:

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath

- Chest pain or pressure

- Loss of speech or movement

For advice on what you should do if you have any of these symptoms, please visit the NHS website (for those in the UK) or consult your local health care provider in your country.

Virology

SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus which belongs to the coronavirus family (Coronaviridae), which is further split into four groups: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus.

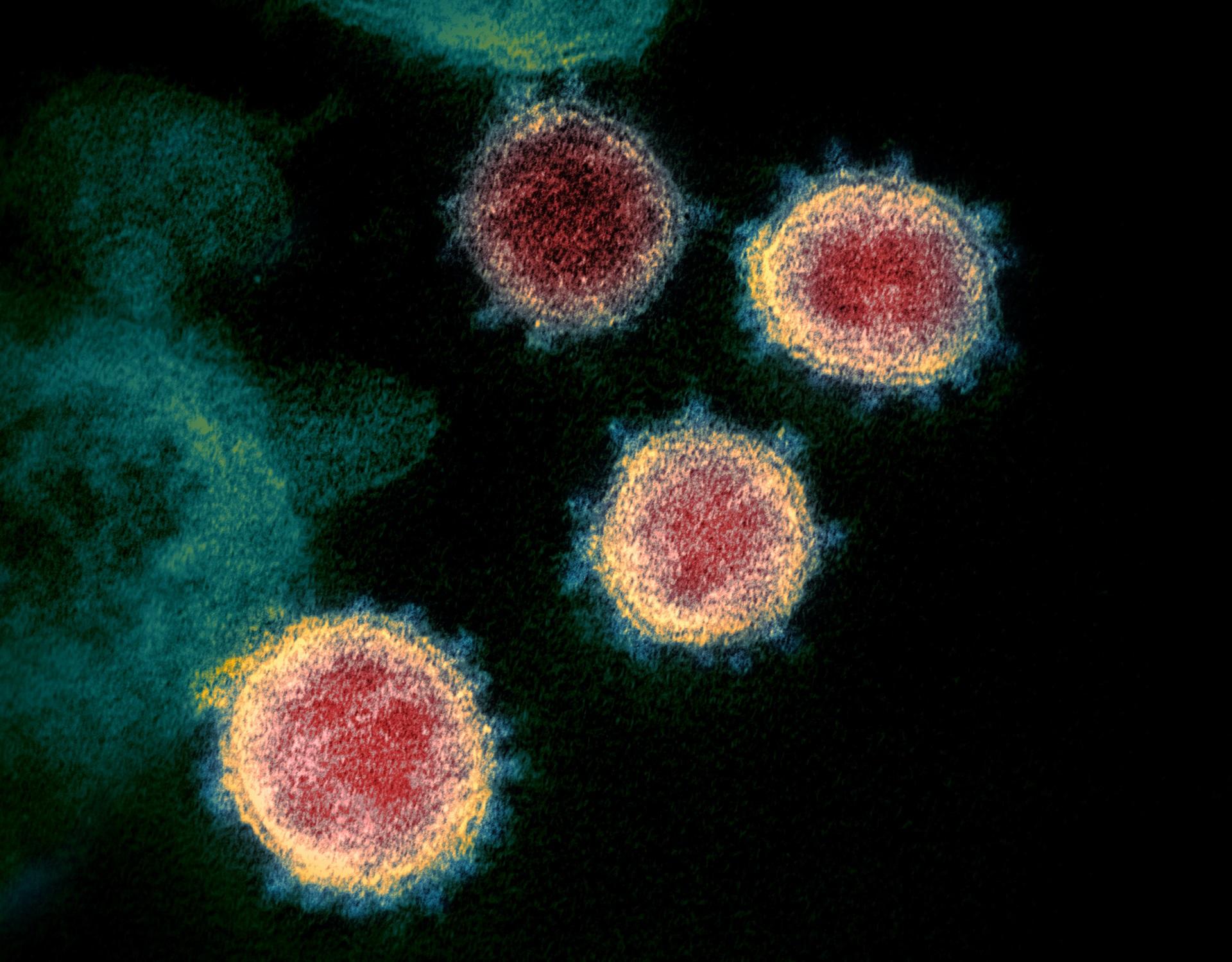

SARS-CoV-2 is a Betacoronavirus. Coronaviruses are named for the crown-like spikes on their surface which resemble the corona of the sun and contain an RNA genome which is protected by an outer envelope with protruding proteins.

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus to emerge and cause respiratory disease in humans.

Pirbright's research on SARS-CoV-2

The Pirbright Institute has a history of working with livestock coronaviruses, primarily focused on studying how coronaviruses replicate and interact with their host cell and developing effective vaccines for infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), a poultry disease that has a huge financial impact on the UK poultry industry.

In collaboration with the University of Oxford, Pirbright successfully demonstrated that two doses of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine produced a greater antibody response than a single dose in pigs. Pirbright is using the same pig model to establish the immune response generated by Imperial College London’s RNA vaccine and Oxford's new potential vaccine, as well as establishing the dosage size that may be needed in order to protect humans. Using the pig model will help to inform the development of vaccines that are both effective and safe for humans.

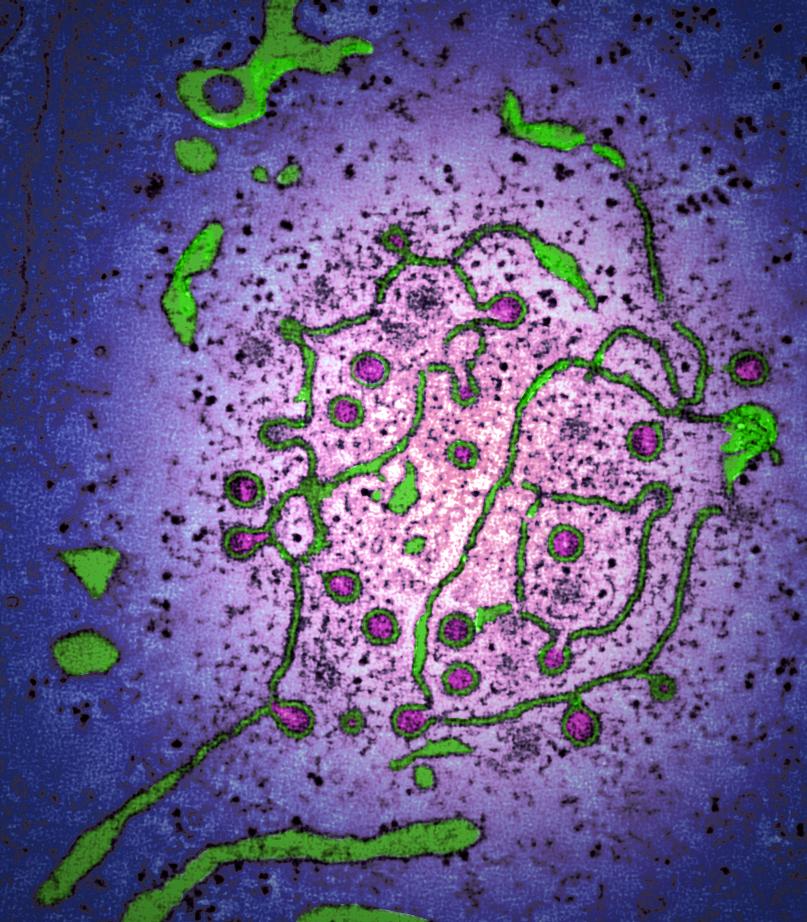

Other Pirbright COVID-19 research projects have explored the mechanisms SARS-CoV-2 uses to enters cells, which have recently demonstrated how SARS-CoV-2 could have adapted to jump the species barrier and which animals could potentially be infected. Work generating reagents and tests to explore diagnostic options for SARS-CoV-2 is also ongoing.

Pirbright is assisting the UK Government during the pandemic by supporting the NHS Berkshire and Surrey Pathology Services (BSPS) and the national NHS Test and Trace programme by providing induction and training for staff joining the new Lighthouse Laboratory in Bracknell. The Institute has also supplied 13 of its high-throughput testing instruments to the UK’s National Coronavirus Testing Centre in Milton Keynes. Over 60 of Pirbright’s diagnostic staff and scientists have also volunteered to join the testing effort at seven Public Health England testing sites across the country and at Pirbright’s local NHS hospital to increase the UK’s diagnostic capacity.

Announced in January 2021, virologists at Pirbright have taken a lead role in a new national research project to study the effects of emerging mutations in SARS-CoV-2. The ‘G2P-UK’ National Virology Consortium with £2.5 million of funding from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) will study how mutations in the virus affect key outcomes such as how transmissible it is, the severity of COVID-19 it causes, and the effectiveness of vaccines and treatments.

Working with lead researchers at the University of Cambridge, our scientists have helped to demonstrate that one of the key mutations seen in the ‘Alpha variant’ of SARS-CoV-2 makes the virus better at escaping immunity and more infectious. This is likely to explain why these deletions are now so widespread.

Pirbright’s research into IBV and other coronaviruses such as porcine deltacoronavirus will continue to further expand our knowledge of how this family of viruses infect hosts and replicate within cells. Building upon this coronavirus expertise, Pirbright scientists will investigate how SARS-CoV-2 replicates and incorporate this into comparisons between other coronaviruses, which could provide vital insights for vaccine and antiviral development. Testing potential antivirals will also form an important part of Pirbright’s SARS-CoV-2 research programme.