Rinderpest, also known as cattle plague, was primarily a disease of domestic cattle, buffalo and yaks, although the disease had also been reported in various wildlife species such as eland, giraffe, wildebeest, kudu and various antelopes.

A 20-year global effort to eradicate the disease has been successful, due to the availability of an effective vaccine and extensive surveillance. As a result, there have been no cases of rinderpest seen since 2001. Rinderpest virus is only the second virus to have ever been eradicated; the first was Smallpox virus in 1980.

The final declaration of global freedom from rinderpest was in 2011 with the eradication of the virus estimated to save the economies of Africa around US$1 billion per year.

Please see the Defra website for advice on how to spot and report the disease in the UK.

Clinical signs

Domestic cattle, buffalo and yaks are very susceptible to rinderpest, with mortality reaching 80%-90% when infected with the more virulent strains of the virus.

- Fever

- Discharge from nose and eyes

- Necrotic lesions on the gums, lips and tongue

- Other damage in the upper and lower digestive tracts

- Enteritis followed by diarrhoea

- Dehydration

- Death

Virology

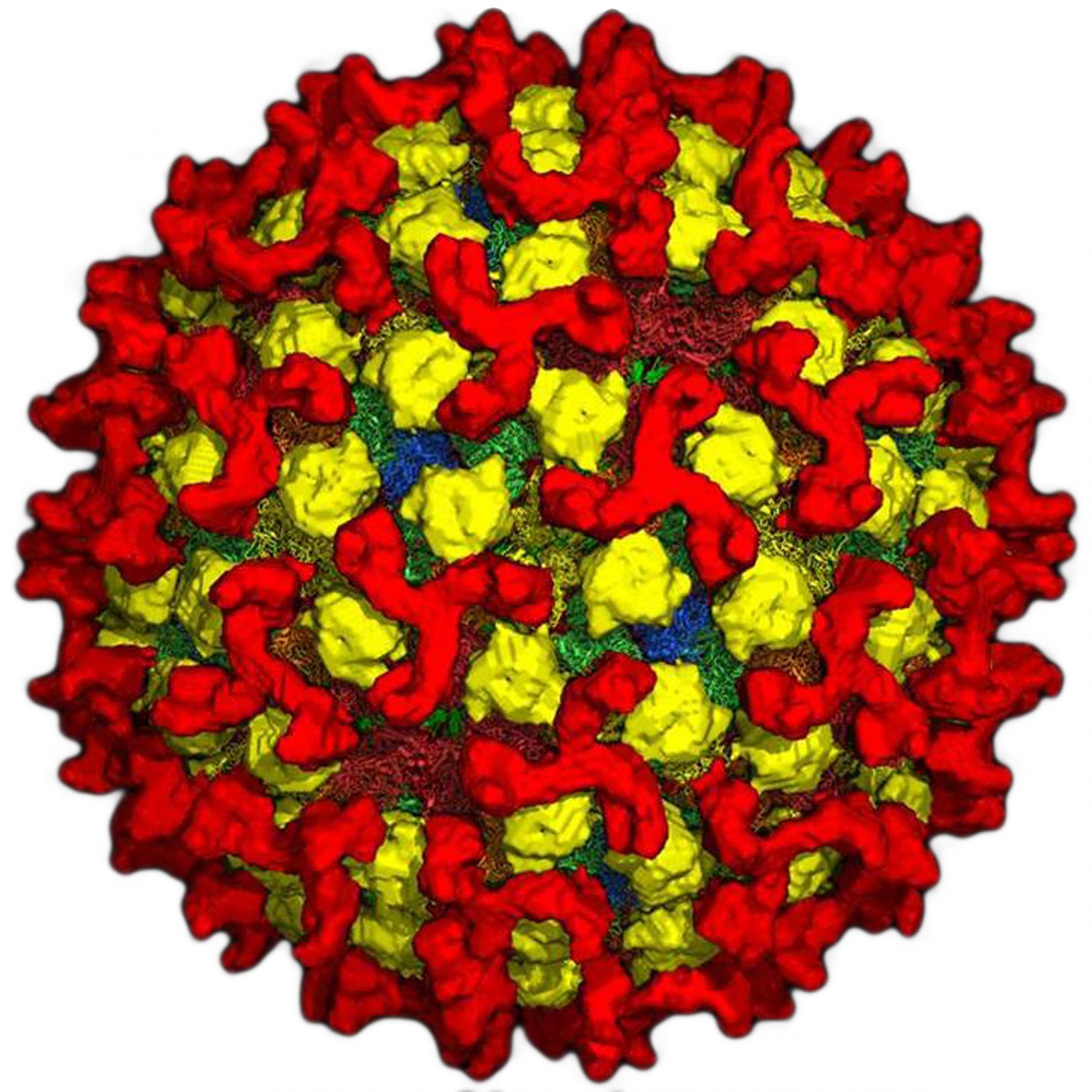

Rinderpest virus (RPV) belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family, genus Morbillivirus. It is closely related to the viruses peste des petits ruminants, canine distemper and the human measles virus.

Rinderpest strains with different levels of virulence in cattle occurred globally and could be differentiated genetically.

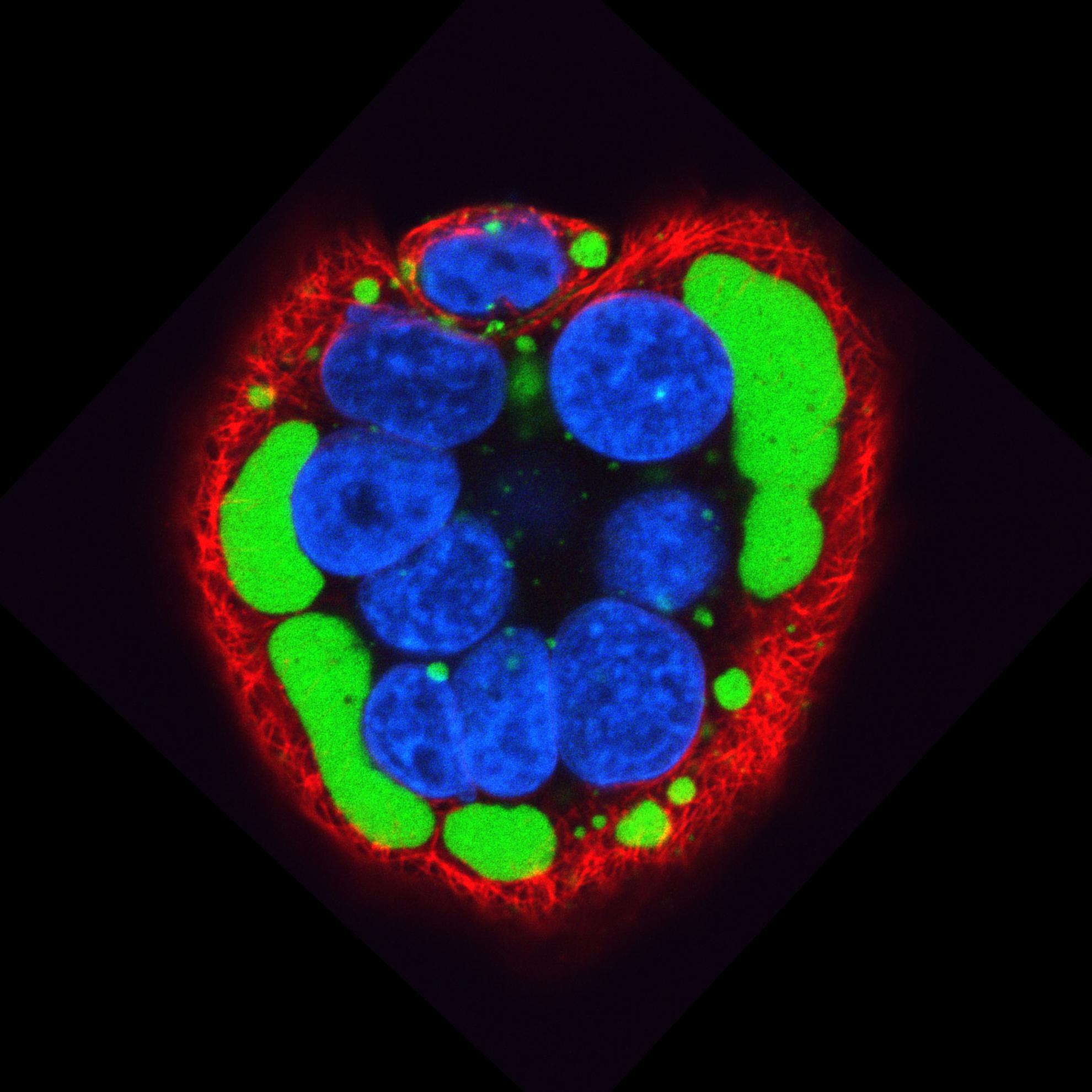

The virus has a membrane envelope and a nucleocapsid which contains the negative sense single-stranded RNA genome.

The widely used RBOK vaccine provided immunity against all known strains of Rinderpest virus and was an important tool in enabling eradication.

Pirbright's research on rinderpest

As a Reference Laboratory for rinderpest, The Pirbright Institute played a key role in aiding its eradication, working closely with the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH).

The Institute developed the main tools used for disease diagnosis and surveillance and worked with national laboratories in affected countries to ensure those tools were used effectively, as well as providing Reference Laboratory services for confirmatory diagnosis and sequencing where required, enabling affected countries to map the movement of the virus during outbreaks. The Institute also carried out basic research on the biology of the virus and development of novel vaccines and provided support for national diagnostic services, helping with risk analysis and contingency plans in the event of further outbreaks.

This work, as part of a global effort involving mass and targeted vaccination programmes and large-scale surveillance, resulted in the eradication of the disease from all affected countries, with the WOAH formally declaring the eradication of rinderpest in June 2011. Rinderpest thereby became the second virus disease to be globally eradicated, after smallpox.

In the post-eradication era, Pirbright is helping to ensure the world stays rinderpest free. The Institute is one of the few Rinderpest Holding Facilities designated by the WOAH and FAO, and has led the 'Sequence and Destroy' project to eliminate rinderpest samples. Pirbright continues to work with WOAH and FAO to ensure global vigilance in this rinderpest post-eradication era.