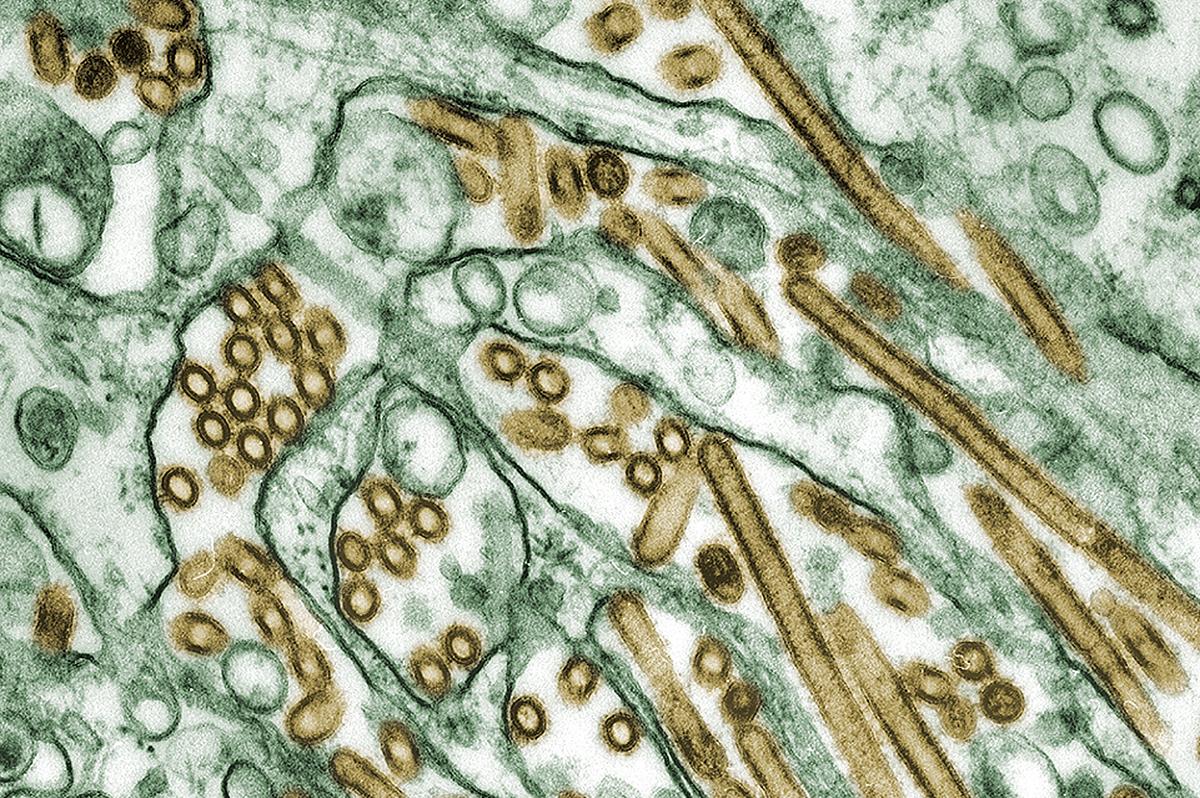

Study highlights evolution of virus and continued risk of spillover to humans.

In 2024, scientists detected an outbreak of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in dairy cattle in the United States. The virus spread among cattle but also spilled back into poultry, wild birds, other mammals, and humans.

Writing in Nature Communications, researchers from The Pirbright Institute and six collaborating organisations explain how the virus rapidly adapted to cattle and gained an enhanced ability to replicate in mammalian cells, including those from humans.

The team studied the B3.13 genotype of H5N1 circulating in U.S. dairy herds and found the virus quickly accumulated specific mutations in its polymerase genes, which are key components required for viral replication after the jump from birds into mammals.

One mutation, PB2 M631L, was found in all cattle virus sequences studied, and another mutation, PA K497R, appeared in the vast majority.

Using genetic, structural, and functional analyses, the researchers showed that PB2 M631L improves how the viral polymerase interacts with a critical host protein called ANP32, especially one bovine version known as ANP32A. The interaction is essential for efficient viral genome replication. As a result, viruses carrying this mutation replicate more effectively in bovine mammary tissue, bovine respiratory cells, as well as primary human airway cultures.

The study found evidence of ongoing evolution of the virus within cattle. Additional polymerase mutations, including the mammalian adaptation PB2 E627K and a repeatedly emerging change, PB2 D740N, increased viral replication in a range of mammalian cells with little or no negative impact on replication in birds.

“Our results show the circulation of H5N1 in dairy cattle is actively driving viral adaptation to mammals,” said Dr Thomas Peacock, co-corresponding author and Fellow at The Pirbright Institute. “This improves the virus’s ability to replicate in cattle and heightens the risk of zoonotic spillover.”

“Infections in humans linked to the cattle outbreak have so far been mild and limited, but the findings are concerning. The adapted cattle virus replicates efficiently in human cells, retains the ability to infect birds and swine, and shows no clear fitness cost that would prevent it from spreading between species,” added Dr Peacock.

“While current evidence suggests it does not yet transmit efficiently between humans, continued exposure and viral evolution increase the risk of further adaptations that could change this.”

The researchers stress the need for ongoing surveillance of influenza viruses in cattle and other animals, especially monitoring changes in polymerase genes that signal adaptation to mammals. They call for the urgent development of broadly protective H5 influenza vaccines for both animals and humans.

The study involved researchers from the Royal Veterinary College, Imperial College, The Roslin Institute, Great Ormond Street UCL Institute of Child Health, MRC University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, and University of Oxford.

For further information about Pirbright’s work to investigating how influenza viruses adapt across species, visit our Zoonotic Influenza Viruses webpage.

Read the full Nature Communications paper

Dholakia, V., Quantrill, J.L., Richardson, S.A.S. et al. Polymerase mutations underlie early adaptation of H5N1 influenza virus to dairy cattle and other mammals. Nat Commun (2026).